No. 172379-199x133,

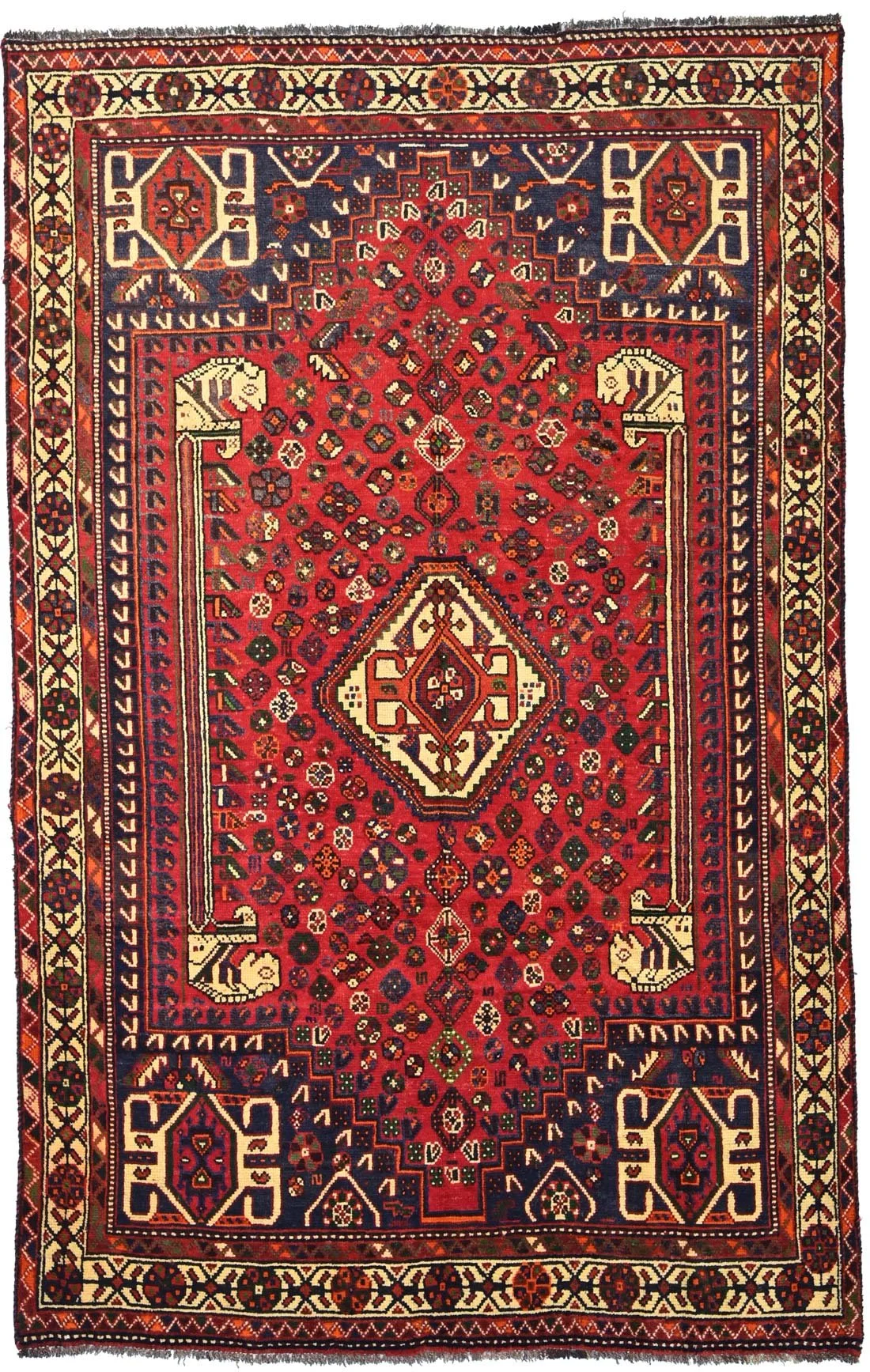

No. 172379 – 199 × 133 cm

A Bidganeh Rug, Circa 1950s

Wool on cotton base

Many village weavers are influenced by the rich legacy of their mothers and grandmothers, faithfully adhering to the family’s or village’s established patterns and colours. Marvels happen when a weaver decides to follow her own way and conceive her own style and design. That is when traditions, folklore, myths, wishes, and dreams begin to dance to the tune of her mind, materialising in the form of the most intriguing and beautiful carpets, such as this gorgeous Bidganeh rug.

This piece presents an unusual interpretation of the “Tree of Life” design, a motif with a history that goes back over 3,000 years. Zoroastrian sources mention the tree as “The Tree of All Seeds,” while the great Persian philosopher of the 12th century, Sohravardi, calls it “Tuba,” both recognising it as the mother of all vegetation in the world.

26562

No. 26562 – 273 × 253 cm

A Bijar- Garrus rug. Handspun wool, natural dyes.

Wool on a cotton base

Kurdish weavers of Bijar are renowned for producing compact and impeccably constructed rugs, so durable that they earned the reputation of “iron rugs” in the market. The piece shown here belongs to the older style of Bijar weaving, known as Garrus, a group celebrated for its natural dyes, refined patterns and remarkable longevity.

Such carpets can endure for decades without fail and grow more beautiful with time. Their enduring strength lies in their sound structure and, above all, in the use of the finest hand-spun wool and magnificent natural dyes. These traditions reach back thousands of years, inherited from their ancestors — the Medes, natives of eastern Mesopotamia on the western slopes of the Zagros Mountains — whose deep connection to nature shaped their materials, colours and aesthetic sensibilities.

No. 20271 – 226 × 156 cm

No. 20271 – 226 × 156 cm

Rahimlu Qashqai Rug, Turn of the 20th Century

Wool on wool base

The great Turkic migrations began in the 6th century and continued until the 11th century. During this time, numerous tribes, descending from the steppes of Mongolia and former East Turkistan (today’s Xinjiang province of China), established themselves across vast regions of Eurasia.

This period marked a profound convergence, where two cultures—East and West—met and shaped one another. The rugged tribes of the East, arriving as conquerors, encountered the refinement and splendour of the Persian and Roman empires. Over decades, their traditions merged, giving rise to distinct new groups, deeply rooted both in their inherited culture and in the lands they came to inhabit.

Among these groups were the Qashqai, who originated in the East, first settled in northwestern Iran, and later moved to the Fars province in the 11th century. Their carpets are vivid reflections of the culture and personality of their weavers, most often women of all ages, who express their sentiments, dreams, and way of life through colours, symbols, and motifs. These are woven spontaneously, drawn from memory and the subconscious, without reliance on naqsha.

This exceptional Rahimlu Qashqai piece bears witness to that tradition, created with hand-spun wool shorn from their own flocks and dyed with natural substances gathered during their seasonal migrations in search of fresh pastures. It stands as both a work of art and a living testimony to a people’s journey.

No. 172380 – 205x133 cm

A Desert-Edge Tribal Rug, Circa 1940

Camel hair and sheep’s wool on wool base

Somewhere on the edge of the desert of Lut in 1940, life was harsh, the land rugged, and every aspect of existence a challenge. Far from the fever of industrialism, the struggles of modernism, and the glamour of city artists, a weaver sat quietly behind her loom.

Her family toiled on the farm, herding camels and sheep, while she worked with yarn spun with the help of her daughters. From camels, she obtained soft, blonde fibres she loved for their touch and colour. From sheep, she gathered coarser wool, which she dyed with hues she prepared herself. Over the fire, she boiled pots of water infused with indigo and madder collected during the past months, transforming the raw fibres into threads alive with colour.

Colours were her delight, her happiness—but she needed only a few. The desert had taught her minimalism, where a single flower in the endless sand seemed like hope, a quiet promise of life. A lover, a mother, and an artist by nature, she began knotting, letting her feelings flow through her fingers into the rug. A few hundred knots in, she dreamed of herself as a bird, soaring high with open wings, her hands dancing as she wove.

Now, in 2023, we can only stand in awe of her creativity, perfectionism, and refined taste, and wonder how high she might have flown had she lived in a different world. And by the way—do you see the birds?

9633

Shahsavan “Lightning Bolt” Rug, Mazlaghan Village

No. 9633 – 197 × 126 cm - Late 19th Century

Wool on wool base

The lightning bolt is the first image that comes to mind when looking at this remarkable Shahsavan rug from Mazlaghan village, and indeed this is the name collectors commonly use for such pieces. The true origin of the pattern remains a mystery, yet one cannot rule out lightning itself as the initial inspiration behind the earliest form of this striking motif, created at an unknown point in the past.

This rug is a fascinating example of the group, enriched with a variety of other stylised symbols, including cypress trees, wheels of time and abstracted forms that reflect a long lineage of inherited imagery. Like many Shahsavan weavings, it was created spontaneously and without a naqsha, the motifs emerging from memory and from the weaver’s subconscious, shaped by traditions passed down through generations.

No. 163208 — 260 × 153 cm

A Kordi nomadic rug, circa early 20th century

Wool on wool foundation

Life is like a carpet, and we are the weavers of its pattern. Some follow common motifs, traditions, and norms, crafting their own predictable and ordinary designs, perhaps elegant and refined in their own way.

For others, weaving becomes an act of rebellion — a personal adventure, fearlessly moving against the currents, defining their own unique patterns, and living life on their own terms. Much like the weaver of this Kordi rug, who created her patterns bold, distinct, and reflective of her journey.

This tribal rug is the work of a nomadic Kordi girl, whose ancestors were relocated to Khorassan province in the late 16th century. Centuries of coexistence with their Turkoman and Baluch neighbours profoundly influenced the Kordi weaving style, producing designs quite unlike those of their cousins in ancestral Kurdistan.

Woven circa 1920s, this piece incorporates cotton into the pile. The use of cotton was a rare and costly choice among the tribe, often reserved for occasions when the weaver wished to demonstrate her wealth and underscore the premium quality of her creation.

133213

No. 133217 — 424 × 337 cm

A Bakhtiar Carpet, circa 1st half of the 20th century

Wool on cotton foundation

Among them, the Luri, Bakhtiar tribes developed a distinctive weaving tradition deeply connected to their landscape and way of life. Until the early twentieth century they lived as pastoral nomads, moving seasonally through the valleys of the Zagros. Their eventual settlement in villages allowed the use of larger looms, and this gave rise to monumental pieces known as “Khan rugs,” commissioned by Bakhtiar Khans for their great tents or urban mansions, yet continuing to embody the spontaneity and heartfelt creativity of smaller nomadic weavings.

This majestic carpet belongs to the ancient Persian garden tradition, a design concept far older than the later chahar bagh. Its compartmental layout reflects the early Iranian vision of the garden as a walled paradise shaped by flowing waterways, channels that brought life, abundance, and order to the landscape. Each panel becomes a self-contained garden: blooming trees, roses, cypress and willow, shrubs, birds, and symbolic motifs woven not with strict geometry but with a village weaver’s imagination and inherited visual memory.

The palette, drawn from natural dyes, carries deep reds, indigo blues, earthy greens, and soft ivory tones that have gently settled over time, giving the rug a serene and dignified presence. What elevates Bakhtiar garden carpets is not only the structure but the soul of the weaver that flows through every compartment, the lived experience of a people whose identity is intertwined with land, water, myth, and enduring craftsmanship.

Although woven for the interior of a mansion, this piece retains the free spirit and emotional depth of nomadic creation. It stands as a remarkable tapestry of nature, memory, and the artistic spirit of the Bakhtiar people.

150608-150x97

No. 150608 — 150 × 97 cm

A Zanjan rug. Circa 1920s

Wool on cotton foundation

Imagine the girl — for it is mostly girls and women who wove such rugs — sitting behind her loom, her hands moving with energy, passion, and skill, tying one knot after another. A few minutes into her weaving, she lets her mind drift, entering a dreamscape as beautiful as the flowers she knots into the rug.

She weaves from what she feels — sometimes utopia, sometimes melancholy, and countless other shades of emotion her subconscious brings forth. The result is not merely a rug, but a reflection of her inner world, a creation infused with her deepest feelings. Passion and exuberance are intertwined in every warp and weft.

This remarkable piece was woven by a weaver of Shahsavan descent in the province of Zanjan, northern Iran.

No. 171111 — 210 × 102 cm

A Ferdows Baluch rug, circa mid-19th century

Wool on wool foundation

The richness of Persian literature has long inspired tribal weavers to create some of the most astonishing rugs — such as this charming Ferdows Baluch.

The weaver, most probably a young Baluch girl, has tastefully depicted a love story immortalised by the 12th-century Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi. The poem recounts a tragic love triangle between the Sassanid king Khossrow II, the Armenian princess Shirin, and Farhad, a humble mason.

This tale of love, devotion, and heartbreak has been recited by elders to their grandchildren for centuries. In the time when this rug was woven — and even today — the story continues to resonate deeply with the lives of many young women whose fates are still bound by tradition and inherited custom.

172381 – 197 x 130 cm

No. 172381 — 197 × 130 cm

A Lori tribal rug, circa 1930s

Wool on goat hair base

Regardless of our opinions, it is always fascinating to observe the remedies and protections that early societies devised against the evil eye — and how people, even in modern times, continue to rely on them.

One of the most intriguing results of ancient superstition is the creation of amulets. The earliest known anti–evil eye charms, dating back to around 3500 BC, were discovered in Tell Brak, Syria. Since then, countless talismans and artefacts have been crafted to counter the power of the “eye.”

The Persians were no exception in their belief in charms and amulets. What distinguishes them, however, is their artistic ability to integrate a wide range of protective motifs into the design of their rugs — as seen in this old Lori nomadic piece, woven circa 1920s.

One can only imagine how beautiful and cherished the girl who wove this rug must have been, carefully incorporating so many protective symbols to shield her life from the unseen forces of envy and misfortune.

25538

No. 25538 — 294×152 cm

Antique Bakhtiar Rug, circa early 20th century

Wool on a cotton foundation

Antique Bakhtiar rugs like the one here, woven in the western foothills of the Zagros Mountains, represent one of the richest expressions of village and tribal artistry in Iran. They arise from a weaving culture in which designs are created from memory, shaped by inherited traditions and by the weaver’s own subconscious, a reservoir of imagery carried across centuries. Living in a landscape where nature, myth and memory coexist, Bakhtiar weavers translate this deep connection into rugs that blend arcane symbols with aesthetic abstractions of trees, flowers, animals and architectural forms, many of whose meanings echo distant times.

Among the most cherished motifs visible here is the sarv, the cypress tree, an ancient Persian emblem of freedom, beauty and longevity. The colours of this rug, derived from natural dyes, have aged with remarkable grace, settling into tones that reveal the astonishing beauty only time can produce. This is a piece that would stand proudly in the collection of any aesthete, exuding charm, character and cultural depth.

163202 155x270

No. 163202 – 270 × 155 cm

Kurdish Tribal Rug, Wool on Wool

The aesthetic appeal of a tribal rug can be enhanced a thousandfold when one comes to discover the history of the people responsible for its creation, the archetypal significance of the motifs, and most importantly, the reflection of the weaver’s personality in the rug. While history and motifs can be interpreted through study and research, the weaver and her psyche often remain a mystery — an intriguing subject open to interpretation and speculation. Perhaps it is this very mystery that makes rugs like this so appealing to those who look beyond appearances and seek inner beauty, whether in objects or in people.

This rug is woven by Kurds of Khorassan, natives of western Mesopotamia and eastern Iran, whose turbulent history stretches back as far as 600 BC. The Kurds of Khorassan are the descendants of those who were forced to migrate eastward during the 16th century by King Tahmasp, to defend Persia’s eastern frontiers against warriors from Central Asia. Since then, the tribe has roamed the green pastures of Khorassan, mingling with Turkomans, Baluch, and Afshars, and in the process forming a distinct identity. Their weavings reflect this evolution, carrying motifs borrowed from neighbouring tribes while remaining true to their Kurdish heritage.

The most remarkable feature of this rug is the presence of a tamgha, repeated in the inner border. This presents another puzzle, as tamghas are traditionally the insignia of Turkic nomads of Central Asia. Perhaps it points to intermarriage and a hybrid cultural legacy among the Kurdish tribes, Turkomans, and Afshars.

A wever from Zanjan.

Shahsavan’s ancestors were nomadic tribes who roamed vast lands from east to west. They began settling in villages from around the mid-20th century, gradually adapting to life as farmers in small communities. Yet their spirit remained unchanged, free, untamed and rich in imagination.

They are responsible for creating an extraordinary form of art, one that reflects an ancient culture shaped by enduring myths and legends.

160645 200x135

No. 160645 – 200x135 cm, An Armenian Qazwin Rug

Wool on cotton foundation. Circa early 20th century.

There are moments in the history of weaving when the conditions that shaped a creation are so particular, so intertwined with a specific community and time, that they can never be repeated. The Armenian rugs woven in the Qazvin region and its surroundings belong to this rare category.

The Armenian community in Iran, long admired for its dignity, culture and artistic sensibility, contributed profoundly to many crafts. As families gradually migrated to larger cities such as Tehran, Tabriz and Isfahan, their weaving tradition in this region slowly faded, leaving behind only a handful of pieces that testify to their refined taste and creative depth.

This exceptional rug, woven near the village of Kharaghan, reflects that heritage with remarkable subtlety. Its harmonious composition blends the distinctive Armenian aesthetic with the artistic language of the local culture, resulting in a piece that feels both rooted and quietly distinct. Central to the design is the repeated “sarv”, the cypress motif, an ancient emblem of freedom, beauty and longevity, rendered here with rhythmic elegance.

A rare survivor of a vanished weaving chapter, this rug stands as a gentle yet powerful reminder of a community’s artistry and its enduring contribution to Iran's cultural landscape.

No. 163220 — 216 × 154 cm

A Kordi rug. Circa late 19th century. Wool on wool base.

This antique tribal rug is more than a woven floor covering, it is a fragment of a world we can only dream of, a time when weavers were true masters of their looms. They worked with love and passion, pouring their feelings into traditional patterns yet freely manipulating them to create designs that sprang from their own will.

The creator of this piece has left her essence in its honest, free, and unrestrained design, unconcerned with markets, trends, or outside expectations. She wove far from the noise that surrounds us today, guided only by her own imagination and spirit.

To sit upon this rug, to feel its texture and sense the vivid aura of the young weaver who created it more than a century ago, is to experience a rare escape. It invites one to leave behind the clamour of the modern world and to dwell, even for a moment, in a space where authenticity and soul endure.

Are these the final thirty?

Did the weaver of this rug know the legend of the "Conference Of The Birds" (منطق الطیر) by the Sheikh Farid al-Din Attar Nishaburi? The story in which thousands of birds set on a journey in a quest for the supreme being (Simorgh). After much suffering, only thirty of them (the number of the birds on the rug) reach destiny and discover the truth. Is this a reinterpretation of the story by the weaver?

Regardless of the answer, many weavers of the Persian rugs have woven their rugs based on a rich culture and fascinating wealth of folklore and literature. That is a fundamental reason for how these rugs appear so far more elegant, mysterious and superior. To appreciate the beauty of a Persian carpet, one ought to look beyond their surface and know the ancient culture and people who have created them.

There in the Simorgh's radiant face they saw

Themselves, the Simorgh of the world – with awe

They gazed, and dared at last to comprehend

They were the Simorgh and the journey's end.

The rug is a Qashghai tribal rug. Circa 1950s

For further study on the story, you may refer to "The Conference of the Birds" by Attar and translated by Sholeh Wolpé.

Village weavers are inheritors of a long tradition. Their designs are often habitual, learned from their elders, while their subconscious minds hold reservoirs of collective memories that go back hundreds of years. These memories are enriched by their own sense of aesthetics, shaped through living and working in beautiful natural surroundings, far from the noise and distractions of large cities.

No. 163585 – 200 × 128 cm

A Sistan Rug, Circa 1940s

Wool on cotton base

The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings) is one of the most celebrated works among Persians. For centuries, its stories have inspired artists, including village and tribal weavers who came to know the epics through bards travelling from place to place, reciting the tales in captivating ways.

One of the most well-known episodes is the tragic battle between Rustam and Sohrab. Before Sohrab’s fatal clash with Rustam, he encountered the fierce resistance of Gordafarid, the lady warrior of ancient Iran. Gordafarid, often described as a lioness, stands as one of the most iconic figures in the Shahnameh and is remembered as a symbol of courage, strong women, and resistance against evil forces.

Sistan, according to Ferdowsi (940–1020 AD), was the kingdom of Rustam. The legend has deeply influenced the weavers of the region, who often create their rugs spontaneously, weaving entirely by heart. This carpet is a remarkable example of such tradition, depicting Gordafarid on horseback and standing tall in various dresses, each adorned with stylised forms of the Farvahar, set among trees of life.

No. 166954 — 165 × 120 cm

Luri Mule Trapping, circa 1930s

Wool on wool foundation

The lifestyle of pastoral nomads has always aroused the curiosity of the landbound folk — their constant movements, and their spontaneously ingenious craftsmanship in producing tools and utility items from their limited resources.

The mule trapping shown here is one such example. Such pieces were woven on portable horizontal looms, using yarn spun by hand and designs drawn entirely from memory — personal or collective — echoing from the depths of the weaver’s subconscious.

This piece was originally folded and bound at the sides to form a large trapping. It was woven by the Lurs, who are believed to be among the native peoples of Iran for thousands of years.

Weavers from The village of Aghja Ghaya in Zanjam province.

Old blood runs deep within the people of this land where the history goes back thousands of years. The fertile crescent and western Macetonemia were where the agricultural societies started cultivating lands and built their villages over 7000 years.

A lot has changed since then, but these people continue their dwellings with care. They work hard from dawn to dusk to earn an honest living. They respect nature by giving and taking without exploiting and polluting.

While at home and not having the farm work, especially during the harsh winters, they spend their time in front of their looms to translate their thoughts, stories and dreams into colourful motifs of their rugs.

No. 134398 — 123 × 191 cm

An old Zanjan rug, circa 1940s

Wool on cotton foundation

This lovely Persian rug belongs to the group of weavings commonly known as Musel carpets. Such rugs are the work of weavers who create spontaneously, following their own interpretations of traditional designs inherited from their ancestors and engraved into their subconscious.

This particular piece is the work of an experienced weaver from the village of Hopa, who poured her heart and soul into what she believed would be her long-lasting legacy. The use of handspun wool and natural dyes, together with a sound structure and firm knots, has given this rug the strength to endure. With time, it has matured gracefully, becoming even more stunning in its present state.

No. 172383 – 173 × 90 cm

No. 172383 – 173 × 90 cm

A Baluch Rug in Tree of Life Design, Early 20th Century

Wool on wool base

The Baluchi tribes of eastern Iran are renowned for their mastery in weaving rugs with a minimal palette and designs of striking simplicity, yet profound meaning. This skill is an inheritance from their ancestors, who have lived in the region since the Palaeolithic era, leaving traces of myth and memory woven into their art.

This elegant piece presents a “Tree of All Seeds” design, more commonly known as the Tree of Life. At its crown rests a highly stylised Simorgh, the phoenix of Persian mythology, while other birds perch along the lower branches. Both the tree and the Simorgh are enduring symbols from ancient myths, engraved in the collective subconscious of the people and materialised in Baluchi weaving.

The rug was woven in the early 20th century with camel wool. Its field is composed of raw, un-dyed yarn, while the motifs were brought to life with hand-dyed threads coloured through traditional methods passed down for generations.

144101

No. 144101 258x175cm

Qashghai tribes, Southwest Iran, Circa 1950s

Wool on wool foundation

Among the wealth of arcane symbols, aesthetic abstractions of nature, and inherited motifs whose significances are often lost in time, stylised motifs inspired by the weavers’ own observations add a less mysterious yet deeply interesting layer to their creations.

This is where mystery, history, and artistry meet and converge into amazing nomadic rugs like this Qashqai, whose creators pass by the ruins of Persepolis during their seasonal migrations and reflect the astonishing columns of a palace from within which Persian Kings of the Kings, like Cyrus the Great, ruled the world for a substantial time from 500 BC, a palace that still inspires the minds and rules the hearts of the Persians.

147967-346x267 . An old Suma (Heriz area) . Circa 1940s

59023-442x327

No. 59023 — 442 × 327 cm

A Yalameh carpet, circa mid-20th century

Wool on wool foundation

Significant transformations occur in the weavings of nomads once they settle in villages. Among the most conspicuous changes is the size of their carpets, which often become considerably larger and more conventional compared to their nomadic counterparts.

This transformation can be attributed mainly to the looms. Nomads typically use small, portable, rudimentary looms — two wooden poles fixed horizontally to the ground, supported by stones and spikes — where the weaver sits to create her rug. In contrast, when they settle in villages, they adopt larger, more complex looms, permanently placed within their homes.

The carpet here is one such example, woven by the Yalameh tribes who have now settled in the villages of northern Fars province. Their weavings retain the ancestral symbols of their nomadic past, yet display a more orderly and expansive composition, reflecting the influence of their settled life.

The Yalameh people are known for using exceptional quality wool, often sourced from their nomadic relatives who roam the highlands during spring and summer. This fine material lends their carpets an extraordinary texture and natural lustre, hallmarks of their enduring beauty.

No. 71689 — 137 × 90 cm

An antique Seysan rug, Cirva 1900.

Wool on cotton foundation

Seysan was once a village near Tabriz, but it no longer exists. Its residents, primarily of the Bahá'í faith since the late 19th century, faced unfavourable policies from local governments and prejudice from neighbouring villages. Over time, these conditions led to migrations, gradually leaving the village deserted decades ago.

The villagers of Seysan were known for producing carpets like the example here, which were far superior in workmanship and colour compared to those from other villages in the area. The patterns of these rugs often featured stylised, archetypal motifs, such as the mother goddess design seen in this particular piece.

The yarn used in these carpets was of outstanding quality, a result of the altitude and rich grazing land where the sheep, whose wool was used, lived. The yarn was dyed using purely natural materials, including madder root, indigo, prangos, and walnut skins.

Rugs from Seysan are extremely rare and highly collectible. This particular piece is even more desirable to connoisseurs due to its highly unusual size, making it a true treasure for collectors.

19412 209x130, A Bakhtiar Persian rug

No. 19412 — 209 × 130 cm

A persian Bakhtiar, circa 1980s

Wool on goat hair base

This rug is remarkable due to the weaver's exceptional skills in portraying a traditional design and even more so for its incredibly creative colour combination. It is a piece that can endure for decades, growing more beautiful with age and use.

Crafted by villagers at the base of Mount Zagros, this rug carries a nomadic legacy as ancient as the civilization of western Mesopotamia.

No. 64366 — 192 × 129 cm

A Shahsavan rug, circa early 20th century

Wool on a cotton foundation

Culture doesn’t grow on trees; it rises from the memory of generations who have lived it. For thousands of years, a collective memory has accumulated through migrations, battles, the rise and fall of empires, invasions, and disasters — in short, through the human struggle to live.

Such is the story of the people who inhabit the old lands of the Persian Empire — like the weavers of this beautiful rug. Its creators, the Shahsavans, are Turkic tribes whose allegiance in the late 16th century led to the establishment of the Safavid dynasty, under which arts flourished and artists prospered.

This rug stands as a reflection of an ancient culture and the outcome of centuries of practice and inherited knowledge. The materials used are of the finest kind — hand-spun wool dyed with natural vegetable colours — woven with precision and devotion. It is a beauty that endures through time, glowing with a quiet, lasting charm.

No. 162768 – 208 x 153 cm

No. 162768 – 208 x 153 cm

A Lori gabbeh. Wool on wool foundation

Nomads of southern and central Persia gathered indigo and madder during their seasonal migrations toward the Persian Gulf. As a result, shades of red and blue became dominant in their weavings.

They dyed their yarns in small batches over wood fires, often using cooking pots. This led to variations in hues that might seem like imperfections to some, but for many, these irregularities create an irresistible charm and a vibrant glow.

This Lori rug is a perfect example. Its radiance and wonderfully minimalistic pattern have helped it defy time. It still commands attention in contemporary spaces.

One never tires of looking at pieces like this, nor of caressing them for their tactile beauty and heartfelt texture.

No. 148147 – 219x159 cm

An Afshar Sumak-Kilim. Wool on wool foundation.

Beware!

Oh you, the cameleer — go gently,

for the calm vacates my soul with thy caravan,

and the life I had

goes with my lover,

its taker.

Camels have symbolic meanings in Persian literature, always representing the long journeys and the beloved’s departure. At the same time, they are celebrated by the nomads of the East for their endurance, without which the trade along the Silk Road between the East and West through the fierce deserts would have been impossible.

The rug here features the animal in a charming manner. The weaver, an Afshar girl, has formed a caravan around the rug by joining multiple camels. Perhaps the young girl was longing for the beloved who was on a long journey.

The craftsmanship is remarkable, demonstrating the weaver’s proficiency in two different techniques and their simultaneous use, which is not an easy endeavour.

5003 122x190

No. 5003 – 122 × 190 cm

Wool on cotton foundation

There are rugs that remain mysterious for the designs they present—often visual abstractions of inner ideas or transfigured symbols passed down through generations. In such pieces, we have no choice but to engage with them on our own terms, interpreting the weaver’s language as best we can.

This kind of mystery creates an intellectual challenge that makes these rugs feel very much alive—continually provoking the imagination and whispering silent stories to the curious eye.

Such is the case with this fascinating late 19th-century Malayer. If our interpretation is correct, the central motif is a lion’s face abstracted into the form of a stylised flower, flanked by cryptic symbols on either side, surrounded by a field of ancient fish motifs, and framed by a border of stylised turtles.

This rug will never stop teasing its owner. It’s a gateway to myth and memory—a quietly poetic companion for anyone drawn to mystery and meaning in handwoven art.

No. 160460 — 342x250 cm

A Josheghan. Circa 2nd half of 20th century. Wool on cotton base.

This Josheghan village rug represents one of the most recognisable and historic Persian rug traditions. Josheghan, located on the edge of the central Iranian plateau, has long been celebrated for its geometric Persian rugs woven entirely from memory, a technique passed down for centuries. This piece features the iconic Josheghan jungle design, distinguished by its stylised tree motifs that trace their origins back more than 400 years.

The stepped diamond medallion and the rhythmic, geometric layout reflect the classic Josheghan aesthetic, rendered here in naturally dyed wool with deep reds, indigos and ivory tones. Woven on a durable cotton foundation, this handmade Persian rug is both visually striking and structurally robust, making it an excellent choice for collectors or anyone seeking an authentic, long-lasting piece for their interior.

Josheghan rugs are prized for their cultural authenticity, their symbolic motifs and the remarkable skill of the weavers who created them. This example captures the timeless character, artistic value and enduring appeal that make Josheghan rugs among the most sought-after Persian village weavings.

160460 342 x 250

71700 103x138cm